Rarely do I agree with more than one politician at one time, on one topic, but…

Susan Rice:

The reality is, the absolute only way to achieve our goal [of] two states living side by side … is through direct negotiations… There is no short cut.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ro8MeyM7mFE[/youtube]

Mahmoud Abbas:

No one can isolate Israel. No one can delegitimize Israel. It is a recognized state… We want to delegitimize the occupation, not the state of Israel.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_ASOBTKpCeU[/youtube]

Indeed, the Palestinian Authority (PA) can no more seek to deligitimize Israel than they can pose an “existential threat” to the state with the occasional Katyusha rocket. Unfortunately, theres not much more I agree with Abbas on.

Much as it pains me I’m even “agreeing” with Netanyahu on minor points. I agree with the conventional wisdom on this issue.

As overdue as I may think Palestinian statehood is (especially post-Oslo, and post-2003), the idea of getting it by end-running Israel at the UN is ill-advised. The fact that Israel offers so many intractables, particularly at present, is no excuse; a creation of a “state” in that body without the full cooperation of the other players in the equation, especially Israel, still means they will ultimately need those players “playing ball”. Quasi-legitimacy may introduce more problems than it solves–and given the regional realities, quasi-legitimacy is all the UN can confer. And reversing the order might just make the next step more arduous. This is not to say Israel is even close to ball-playing.

The PA will reportedly first make their application for full UN membership (making them a de facto state) at the Security Council. The US would veto the application, and and have been forced to show its hand. As unfortunate as I think that is, let’s not forget that these moves, their unpopularity, and the theatrics preceding them are similar to Israel’s 1948 moves at the UN.

I doubt there will ultimately be a UNSC vote on full membership, though. The “best” that can be hoped for at this point is some arrangement that will keep the PA from submitting and instead pursuing some face-saving measure short of the pursuit of full recognition in front of the General Assembly (which as an act of good faith the US and Israel should both vote in favor of in exchange for a good-faith return to negotiations on the part of both parties). At the UNGA, the best they can hope for is to be promoted from “non-member entity” to “non-member state” status (like the Holy See, i.e. The Vatican,) which would–among other things–leave them just where they’re sitting now.

Legitimacy and Law

The elevation of Palestine to a “non-member state” at the is unlikely to afford the PA the leverage that status would afford relative to the negotiating challenge they now (and would still) face. Though it would give them access to ostensible levers only available to states such as the International Criminal Court (ICC), to employ them would be a mistake. If one of their first moves as a state would be to provoke action by the ICC to investigate Israel’s Operation Cast Lead in Gaza, such a move would make Netanyahu–or Israel in general–more difficult to negotiate with (this is not to justify Cast Lead), which would them further back than they started. Regardless of their standing at the UN, they still need to work out innumerable practical issues with their “neighbor”. And they unfortunately can’t do this without the US. Or the people of Palestine (although the IDF’s promise to regard such an act as “war” fleetingly makes me feel galvanized, too)…

Guy Goodwin-Gill, a law professor at Oxford, brings up some questions that might have the PA considering this a hasty pursuit of statehood:

What we have here, it seems to me, is a moment in which certain matters have just not been thought through. Historically, the PLO has been the sole, legitimate representative of the Palestinian people, internationally and within the United Nations [UN]. Now it is to be the state. Who, though, is the state, and what are the democratic links between those who will represent the state in the UN and the people of Palestine? An abstract entity – a state – is proposed, but where are the people?

One issue here is that the majority of Palestinians are refugees living outside of historic Palestine, and they have an equal claim to be represented, particularly given the recognition of their rights in General Assembly resolution 194 (III), among others. It is not clear that they will be enfranchised through the creation of a state, in which case the PLO must continue to speak for their rights in the UN until they are implemented.

Professor Goodwin-Gill’s paper can be found here.

Put simply, Abbas is not the legitimate leader of the people of Palestine.

I’m “not unfond” of the Quartet proposal being lobbied by their envoy Tony Blair:

Under Blair’s proposal, the Palestinians would indeed present their bid for statehood, but to UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon. Mr. Ban would take the proposal under advisement, with a commitment to present it for a vote in the General Assembly by the end of the year if the Israelis and Palestinians have not returned to direct negotiations by then.

Israel’s Diplomatic Isolation

Israel’s increasing isolation in the region only adds more wrinkles and will likely cause Netanyahu to dig in and get more intransigent rather than less. Their on-again/off-again relationship with Turkey is waning and their embassy in the post-Mubarak Egypt has just been attacked. Things are sketchy on the Northern border with Syria. Netanyahu’s intransigence on settlements has put him on the outs with the Obama administration, and of course there was the “much ado” business over ” the pre-1967 borders”.

Mitchell’s gone and some the latest moves seem to be backfiring on other envoys in diplomatically spectacular ways:

Speaking to reporters in Ramallah, Nabil Shaath said that a plan delivered at the last minute by U.S. envoys David Hale and Dennis Ross did not meet several Palestinian demands, thus convincing Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas that the U.S. was not serious in trying to negotiate peace.

Talk about waning influence…

I am not surprised the Palestinians are frustrated.

Two Palestines

Since mid-2007 there have been two Palestines to match the geographic separation. Unable to agree on a government (among other things), Hamas withdrew to “govern” Gaza exclusively and Fateh continued to manage the West Bank. The convenient withdrawal of Hamas is one set of circumstances that led to Cast Lead. With Egypt set to be under new management, the position of Gaza and the Egypt-Israel accord seems slightly more tenuous–this is just one circumstance driving the will to “unity”.

I began putting down notes on this topic after the Fateh/Hamas deal, first intending to post immediately after and then well ahead of the UNGA meeting and whatever move the PA made. Alas, the 11th hour has arrived…

At the time, Matt Duss wrote:

As for Hamas, the key question is why now? Hamas’s strategy thus far has been to sit back and watch Fatah fail, let the peace process crumble, and remain standing as the only viable Palestinian alternative. Going for this deal now indicates that they feel they have something to lose by continuing to stand aloof. The change to an Egyptian government less willing to rigidly enforce the United States and Israel’s red lines was also almost certainly a contributing factor.

Further, Hamas has seen its support among Gazans drop considerably. Shikaki’s polling shows “50% of Gazans are ready to participate in demonstrations to demand regime change in the Gaza Strip,” where Hamas rules, while only 24 percent of those polled in the Fatah-ruled West Bank said the same. It’s also likely that Hamas feels vulnerable with its key Arab ally and patron Bashar al-Assad facing serious unrest in Syria. The growing challenge to its rule in Gaza by even more extreme Salafist factions may have Hamas worried about its future.

The later revelations in the “Palestine Papers” didn’t buy them any special legitimacy at home either.

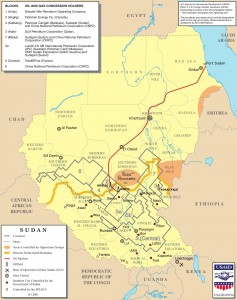

Nation Branding

Al Jazeera blogs on the branding moves a newly-minted State of Palestine would need to undergo, and I can’t help remembering not only Nation Branding but also an earlier post here on that same topic with regard to South Sudan. Palestine is most definitely a nation; unfortunately stamps–in this case probably even UN recognition–do not a state make.