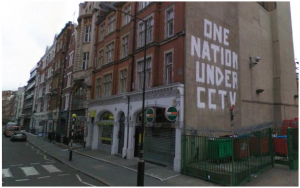

Seeing is knowledge is power…

Panopticon, USA

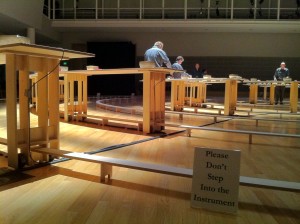

Simplistic to be sure, but one could do worse if pressed for Foucault in five words. Knowledge and power are inextricably entwined, and seeing confers knowledge. Foucault made a trope of Jeremy Bentham’s architectural model, the Panopticon, to embody the role of observation in power relations. The Panopticon centralizes and privileges seeing; because everyone is a potential subject, they become an object of passive cohersion. In a prison designed on this model, the warden, situated in a central tower, could see every prisoner; since no one could be certain whether they were the focus of his gaze, they would regulate their own behavior, almost constantly, without active cohersion (discipline)–in fact, no one need be watching at all (the shelf life of this would, of course, be limited!): the mere threat of being observed would suffice.

…it is at once too much and too little that the prisoner should be constantly observed by an inspector: too little, for what matters is that he knows himself to be observed; too much, because he has no need in fact of being so. In view of this, Bentham laid down the principle that power should be visible and unverifiable. Visible: the inmate will constantly have before his eyes the tall outline of the central tower from which he is spied upon. Unverifiable: the inmate must never know whether he is being looked at at any one moment; but he must be sure that he may always be so. (Foucault, page 201 in the Vintage edition of Discipline & Punish)

The Threat of Visibility

But far more than just the person, the body, can be seen and confer power–all the traces of our lives have this capacity. For example, the immense trove of knowledge (films, photos, wiretaps, recovered mail, even gossip) that J. Edgar Hoover hoarded furthers the possibilities of passive cohersion, and couples control with reconnaisance. The fact that this hoard existed was an open secret, and no one, not even–especially not–the president was immune; any aspect of anyone’s “private” life might be exploited by Hoover or those he deigned to share scraps of this power with. Anyone who knew this might moderate their own behavior lest traces be sucked up by Hoover’s “Hoover”. Failing that, their only recourse would be to carefully manage their relationship with the FBI Director (not the office, but the Director himself).

Information Wants To Be Free

But, in the words of Stewart Brand, “Information wants to be free” (though originally he meant this in terms of expense, not liberation), and apparently it also seeks to liberate itself. And so, with for instance Google Maps/Earth/Street View, we become our own warden. Increasingly there is no single, centralized warden: less and less information is the exclusive property of state-operated agencies (to some degree–what’s worthy of exposé may not be sufficient to locate and destroy Usama bin Laden, for instance). Now anyone, given sufficient means, can acquire commercial satellite imagery (there was a time when the idea of commoditizing these images was contentious–indeed, how much longer will drones remain the sole province of state-run agencies?), or just find it on Google Earth and gain some knowledge worthy of exposure.

Panopticon Now

The contemporary Panopticon is not merely a penal device; not only is it a ubiquitous source of institutional intrusion, it’s also a framework for entertainment:

- Workplace email

- A Supreme Court nominee’s video rentals

- Non-cash transaction records

- Facebook (where we all can watch each other, for fun!)

- Location check-in apps (wave to the Panopticon!)

- Google dependency

- iPhone GPS data storage.

But in popular culture it’s a trope all its own: reality TV (indeed, one of the progenitors of the genre was called “Big Brother”), protagonist/antagonist relationships throughout drama (think Klute, or the classic Lifetime drama, the Eye of Sauron, Rear Window–or just about anything, really).

However, for the purposes of this series, I’ll just focusing on the overhead manifestations, particularly the “democratizing” ones. Satellites, drones, and other forms of aerial sensing might be considered a sort of vertical Panopticon.