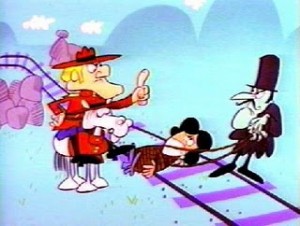

Top hat, frock coat, pale skin, and a long curled moustache. His posture is hunched and he rubs his hands together (antes-hoc plotting) or palms are together, fingers pointing skyward (post-hoc plan success, a sort of malevolent namaste).

The Perils of [Insert Damsel’s Name Here]

This is the villain, Snidely Whiplash edition. While we know him from Rocky and Bullwinkle, he’s a meta-child of numerous 19th and 20th century archetypes of villainy, paticularly In silent film. Snidely’s objectives appear to be more tactical and without broad ambitions: Nell Fenwick serves as a pawn to thwart the Dudley Do-Right’sdoing-right, Dudley’s benevolence is predicated on thwarting Whiplash’s efforts. Feedback ensues, and Nell’s adoration is maintained; in Jungian terms they’re a coniunctio oppositorum.

Snidely’s most infamous act consists of tying Nell to railroad tracks with enormous quantities of rope (really, just binding Nell in a cocoon of rope and laying her across the tracks), thus bringing a modicum of suspense to the story.

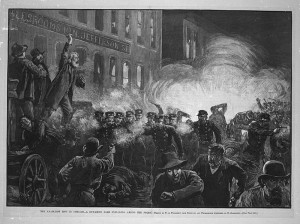

This post-industrial damsel in distress trope appears to have beginnings in a silent film called “The Perils of Pauline”. In a pre-industrial iteration of that trope, Pauline is tied to a log which is conveyed toward an enormous rotating saw (a variation of this appears most recently in Sherlock Holmes, where Sherlock rescues an erstwhile flame from conveyance to a band saw used for sectioning pigs). That’s merely the 20th century cinematic record; earlier versions appeared on stage and in printed fiction.

The Villain’s Wardrobe

The Moustache

The moustache is one key variable in the evil equation (though the value can be 0–take Blofeld again). Moustache >1 is most important when we’re depicting a villain of yore–contemporary bad guys completely unencumbered by past convention don’t rely on them to telegraph their villainy.

The Hat

Snidely accompanies the frock coat and cape with a top hat–this version of the ensemble often includes a cane. In “Coming Out Party”, Snidely and Dudley trade hats and their roles come with the objects rather than inherent ethical motives–Dudley engages in villainous acts and Snidely works to thwart him (go to 12:52 if you prefer not to tolerate the whole thing; if you’ve read this far, I do recommend the Dudley Do-Right episode).

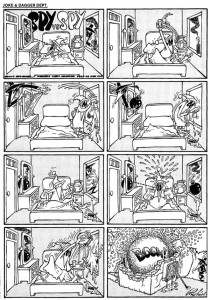

In the case of “Spy vs. Spy”, the morphological congruence is part of the joke, as only colors of their hats and coats (in this case, there’s no moral linkage between the “black hat” and the “white hat”) distinguish them. Indeed, even their actions (which is of necessity partial, the comic panel acts like a telescope with a narrow view) are undistinguished morally. The near-ubiquitousness of objects like the bomb only reinforces the repetitiveness of their relationship. They’re another instance of the coniunctio oppositorum.

The Monocle

Originally more of a symbol of wealth or sophistication (Monopoly, Charlie McCarthy, Mr. Peanut), once it’s common use as an essential eyepiece faded, it became a more niche item to be employed by a certain flavor of villain.

The monocle is so ubiquitous a trapping that a Homestar Runner (I carpooled with Strong Bad for a while, BTW) macro-Bad Guy goes by the name of “Baron Darin Diamonocle”. In fact he carries another character as a pet a la Blofeld.

The Mask

The mask is an essential accoutrement of a certain sort of villain. As a disguise disguise seems to have magical properties; the mere addition of the mask to an otherwise unaltered character seems to have a capacity to conceal far exceeding its surface area.

The mouth-mask is another variation sported by numerous cultural bad guys, and probably one of the oldest in the villainy wardrobe. My most recent exposure is G.I. Joe’s Cobra Commander (the face mask/goggles/helmet combo is a Cobra standard of course).